Introduction

This article discusses access control in RDF graph stores. My interest in this topic arose after reading “What’s in a Pod? – A Knowledge Graph Interpretation for the Solid Ecosystem.”1 Although the article only briefly mentions access control mechanisms, the SOLID protocol itself is designed for the fine-grained access control required by its use cases, which sparked my interest. This contrasts with RDF graph stores, which are triple-oriented and utilize different access control mechanisms.

I was further motivated by a use case in asset management, which requires storing data about objects with varying security classifications. In some scenarios, a full overview of all objects is required, regardless of security classification, while in others (e.g., when a user without proper clearance accesses the data), security must be enforced by filtering out classified objects.

In this article, I will present the current security options in graph stores—focusing on Fuseki, the store I am most familiar with. I will compare them to relational databases to see if those are better suited for such use cases, briefly discuss research done in the Netherlands on the topic, and finally present an alternative approach for access control based on SHACL rules.

Access control in Fuseki

Fuseki uses Apache Shiro for role-based access control (RBAC), configured via a shiro.ini file. This provides security at both the dataset and graph levels.

Dataset-Level Access

This coarse-grained level of access control is managed by matching URL patterns in shiro.ini, thereby securing an entire dataset’s endpoints.

- Mechanism: The

[urls]section maps a URL path to a required permission or role. - Example: To restrict all access to a dataset named

myDBto users with theeditorrole:[urls] /myDB/** = authc, roles[editor]This line ensures any request to

/myDB/*(query, update, etc.) requires the user to be authenticated and have theeditorrole.

Graph-Level Access

This is fine-grained control, applied after the URL-level check. It uses specific permission strings that Fuseki’s security module understands.

- Mechanism: Permissions are defined for roles, targeting specific actions (

read,write,update) on named graphs. - Example: Grant a

readerrole read-only access to a public graph, and aneditorrole write access to a private graph within the same dataset:[roles] reader = read:graph:http://example.org/publicGraph editor = read:graph:http://example.org/publicGraph, write:graph:http://example.org/privateGraph

How It Works

- A user sends a SPARQL request to a dataset endpoint (e.g.,

POST /myDB/update). - Shiro (Dataset Level): Checks if the user is authenticated and has the necessary role to access

/myDB/**. - Fuseki Interceptor (Graph Level): If the request passes, Fuseki inspects the SPARQL query to identify the target graph.

- Shiro (Graph Level): Fuseki checks permissions for the user’s roles on the given graphs.

- Access is either granted or denied accordingly.

Access control in relational databases

Compared to the access control in Fuseki (dataset and graph level), relational databases often offer much finer-grained security options. I’ll use PostgreSQL as an example. The core difference is that PostgreSQL’s security is data-aware, while Fuseki/Shiro’s security is primarily resource-aware (endpoints and graph URIs).

Here is a comparison:

| Feature | Fuseki with Shiro | PostgreSQL |

|---|---|---|

| Granularity | Endpoint (Dataset) & Graph | Database, Schema, Table, Column, Row |

| Mechanism | Config file (shiro.ini) | SQL GRANT / REVOKE statements |

| Paradigm | Application-layer security on API endpoints | Integrated, data-aware security model |

| Smallest Unit | A Named Graph (a collection of triples) | A single cell value (via column/row rules) |

Key Differences & Finer Control in PostgreSQL

-

Column-level security: You can grant a user

SELECTpermission on specific columns of a table while denying access to others. For example, a user can query employee names and departments but not their salaries. There is no direct equivalent in Fuseki; you would have to split sensitive data into separate, secured graphs. -

Row-level security (RLS): This powerful feature lets you create security policies that filter which rows a user is allowed to see or modify, based on attributes or session context. For example,

CREATE POLICY user_orders ON orders FOR SELECT USING (customer_username = current_user);ensures users only see their own orders. Achieving this in Fuseki is far more complex; typically, you must segregate data into different named graphs per user, leading to management challenges.

In summary, PostgreSQL provides a much more granular security model, well-suited for asset management use cases. However, not all relational databases offer this level of functionality—PostgreSQL, Microsoft SQL Server, Oracle Database, and IBM Db2 do, while MySQL, MariaDB, and SQLite do not.

Research

Lock/Unlock

Interesting research was done by the Dutch Kadaster, in the lock-unlock project. Unfortunately, the documentation is in Dutch. I’ll add a translated version of both approaches here.

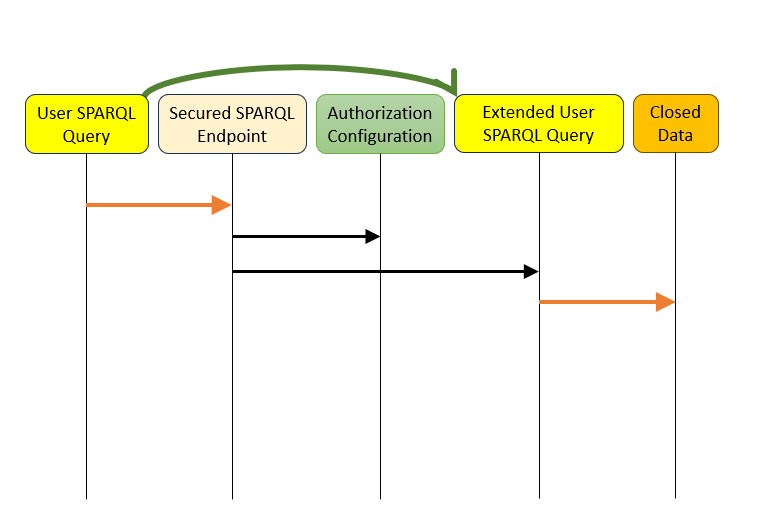

Query Rewrite Approach

The SPARQL rewrite method analyzes incoming SPARQL queries and rewrites them before forwarding them to the triplestore. The user communicates with a SPARQL endpoint proxy that rewrites the query, sends it to the triplestore, and returns the results2.

In concept, the query is analyzed and restrictions are added:

- If the user lacks access to specific graphs, the queries are checked to ensure they don’t access those graphs.

- If explicit graphs are referenced, access is checked accordingly.

- If the query doesn’t specify graphs, allowed graphs are explicitly added so only permitted data is queried.

- Horizontal subsets are enforced by adding filters to exclude unauthorized resources.

- Forbidden predicates are either replaced in the query with non-existent ones or filtered out.

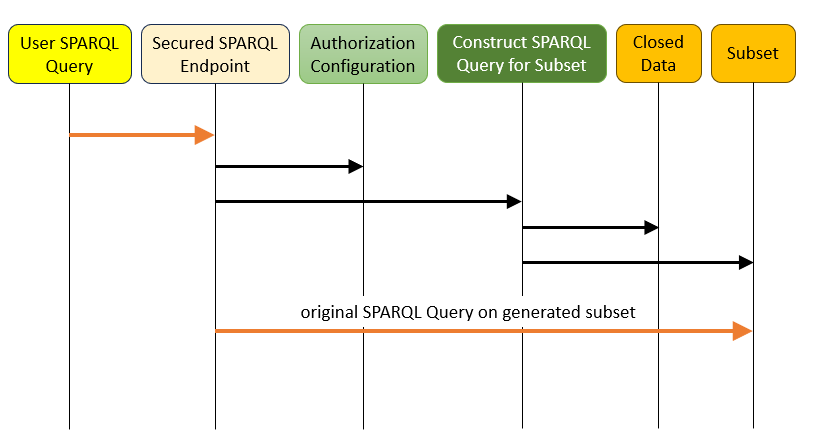

Subgraph Approach

The subgraph method makes a pre-selection based on applicable user rules. The query runs over just this subgraph, making unauthorized data inaccessible. Like the rewrite method, this can be implemented as a transparent proxy endpoint.

Conceptually, the subgraph method works as follows:

- The user sends a query and their authorization data.

- The endpoint determines which authorization rules apply.

- For each rule, it determines which data it grants access to.

- The accessible data from all rules are merged to form a subgraph.

- The submitted query is executed on this subgraph.

- Results are sent back to the user.

Analysis

As the researchers noted, both approaches are feasible but have drawbacks. Query rewriting may alter query behavior in ways users don’t anticipate, and it is difficult to ensure the rewrite fully preserves a query’s original intent.

The subgraph method avoids this, but introduces new challenges: Subsets required must be materialized before query execution. Materializing on-the-fly is slow; pre-materializing requires keeping subsets up to date with the source data, adding complexity.

UTKa research

More work is ongoing at UTKa Data Lab. Although there are not yet many published results, as this is an extension of the Lock/Unlock project, it is worth monitoring.

Other research

Additional research often focuses on query rewriting and analysis. See, for example, SHACL-ACL.

SHACL-based Access Control (SBAC)

The above approaches either require preprocessing of the dataset, or cannot guarantee that changes won’t affect the intended meaning of original queries.

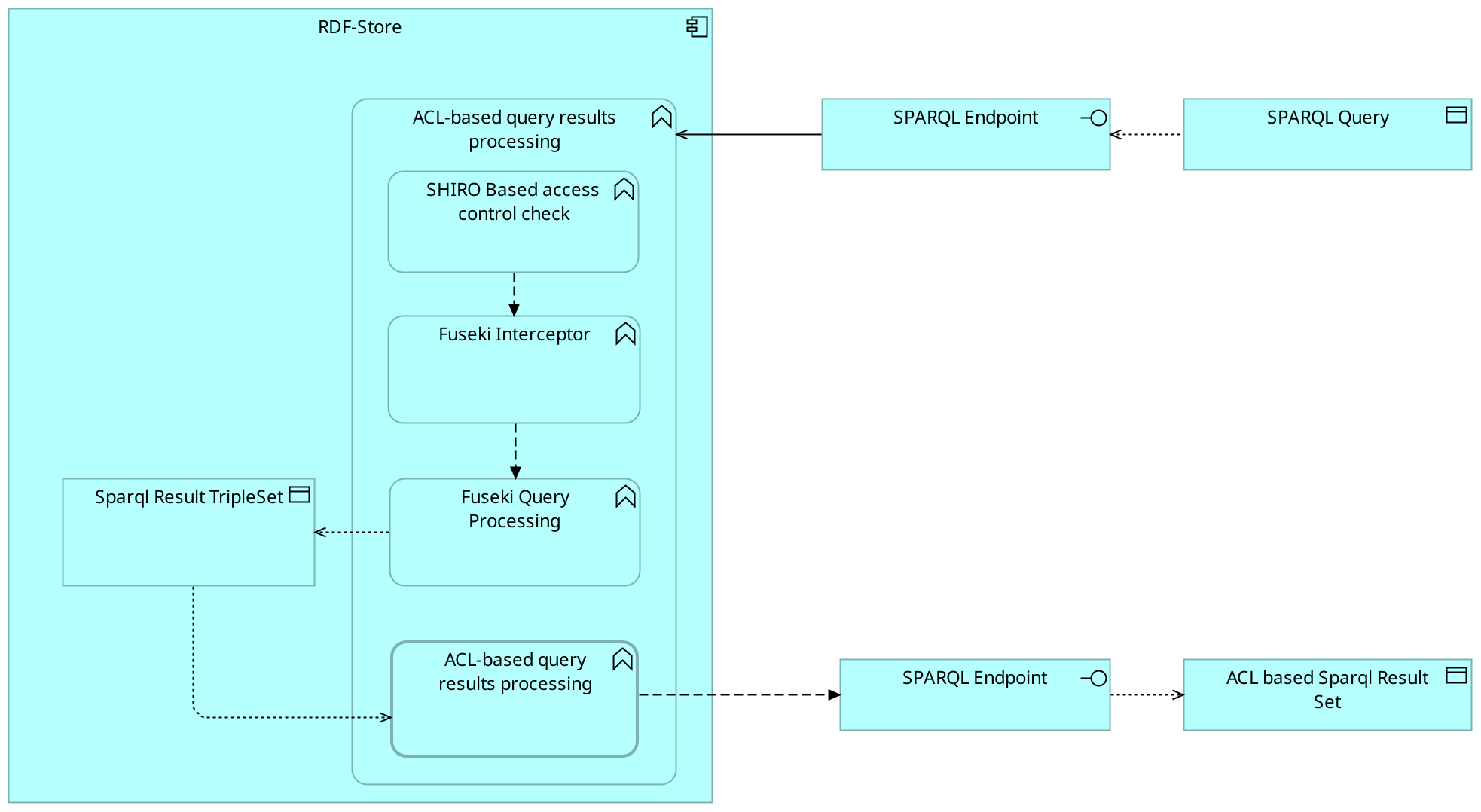

To address this, I propose a mechanism already hinted at in the lock/unlock project: integrating access control into the RDF store itself. SHACL already provides a way to validate whether a data pattern in an RDF store matches a certain constraint.

The main setup:

The new component is the ACL-based query result processing function.

Subject Filtering

The overall approach is: once triples are fetched from storage, for each subject of a triple, a SHACL test (or several) is performed. If the test fails, all triples with that subject are discarded from the result set.

Taking advantage of SHACL

Compared to row-based access control in RDBMSs, SHACL is much more flexible. Whereas relational systems can usually only check within one table per statement, SHACL—especially with SPARQL and property paths—is far more expressive.

Property Paths

Property paths (from SPARQL 1.1) allow definition of sequences of predicates connecting focus nodes to other nodes.

| Property | Path | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence | rdf:type/rdfs:subClassOf | Follow rdf:type, then rdfs:subClassOf |

| Alternative | foaf:knows|foaf:member | Follow either foaf:knows or foaf:member |

| Zero or More | ex:parent* | Follow ex:parent zero or more times (including the node) |

| One or More | ex:child+ | Follow ex:child one or more times |

| Zero or One | ex:related? | Follow ex:related zero or one time (optional) |

| Inverse | ^ex:hasAuthor | Follow the relationship in reverse |

Practical Example

Suppose we have a set of assets, some of which are highly classified, and most are not3:

@prefix rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> .

@prefix ex: <http://example.org/> .

# Define the assets

ex:assetA rdf:type ex:Asset .

ex:assetB rdf:type ex:Asset .

ex:assetC rdf:type ex:Asset .

# Model the security classification for asset C

ex:assetC ex:hasClassification ex:topSecret .

# Define the classification object

ex:topSecret rdf:type ex:Classification .

Suppose assets can have sub-objects:

# Define sub-objects and nesting

ex:assetA a ex:Asset; ex:hasPart ex:assetA_part1 .

ex:assetB a ex:Asset; ex:hasPart ex:assetB_part1 .

ex:assetC a ex:Asset; ex:hasClassification ex:topSecret; ex:hasPart ex:assetC_part1 .

ex:assetA_part1 a ex:AssetPart .

ex:assetB_part1 a ex:AssetPart .

ex:assetC_part1 a ex:AssetPart; ex:hasPart ex:assetC_part1_subpart1 .

ex:assetC_part1_subpart1 a ex:AssetPart .

A sample SHACL shape to flag anything within a top-secret asset or its sub-parts:

@prefix sh: <http://www.w3.org/ns/shacl#> .

@prefix ex: <http://example.org/> .

ex:IsTopSecretShape

a sh:NodeShape ;

sh:property [

sh:path ( [ sh:zeroOrMorePath [ sh:inversePath ex:hasPart ] ] ex:hasClassification ) ;

sh:hasValue ex:topSecret ;

sh:minCount 1 ;

] .

This shape marks all sub-objects of top-secret assets as also top-secret (even when there’s no explicit classification on the sub-object). This goes beyond anything typically possible in a relational database ACL.

User Clearance Example

Suppose users have different clearances:

ex:userA1 a ex:User ; ex:hasClearance ex:topSecret .

ex:userB1 a ex:User ; ex:hasClearance ex:confidential .

ex:confidential a ex:ClearanceLevel .

A SHACL shape can be used to check access:

ex:AccessControlShape

a sh:NodeShape ;

sh:targetClass ex:Asset, ex:AssetPart ;

sh:sparql [

a sh:SPARQLConstraint ;

sh:message "Access denied. User does not have the required Top Secret clearance for this asset." ;

sh:select """

SELECT $this WHERE {

BIND ($this AS ?asset)

?asset (^ex:hasPart)* / ex:hasClassification ex:topSecret .

FILTER NOT EXISTS { $user ex:hasClearance ex:topSecret . }

}

""" ;

] .

How this works:

- If User A1 (with top-secret clearance) queries Asset C, validation succeeds.

- If User B1 (without top-secret clearance) queries Asset C, validation fails.

Further Work

As in the lock/unlock project, a demonstrator could be created pairing queries with a separate SHACL processor, to test if the SHACL-based approach works in practice. If it does, eventually this functionality could be embedded directly in the Fuseki engine for seamless query-time enforcement.

Interesting Topics

- What if queries contain a SERVICE statement? The user context should be passed to remote endpoints, which requires shared authentication infrastructure.

- HTTP response headers could indicate if triples were removed due to access control filtering.

Conclusion

Access control in RDF is currently less advanced than in RDBMS systems. Certain use cases would benefit from a more advanced access control mechanism. In this article, I propose a solution based on SHACL, leveraging its well-established pattern recognition and validation capabilities. This approach avoids the drawbacks of earlier methods (such as complex query rewrites and data preprocessing), although it increases the complexity of the RDF-store itself. Given the advantages however, SHACL-based access control is a highly attractive option.

-

Dedecker, Ruben, et al. “What’s in a Pod? – A Knowledge Graph Interpretation for the Solid Ecosystem.” Proceedings of the 6th Workshop on Storing, Querying and Benchmarking Knowledge Graphs, edited by Muhammad Saleem and Axel-Cyrille Ngonga Ngomo, vol. 3279, 2022, pp. 81–96. ↩

-

The images are taken from the Kadaster website. ↩

-

All examples were AI generated ↩